My thoughts on festivals, filmmaking and my animation heroes....click the links below and read on!

Karel Zeman

We had the incredible good luck to see a beautifully restored print of Karel Zeman's 1961 "The Fabulous Baron Munchausen" on the Criterion Channel (this restored version premiered at the 2016 Telluride Festival). Absolutely amazing in every aspect - and I'm very embarassed to say that I knew little to nothing about Zeman (Czech filmmaker, 1910-1989) before this. Now he's kind of like my hero, based just on this one film. Starring as the Baron, Miloš Kopecký is perfectly cast; pompous, elegant, endearing, ingenious. But really it is the visual experience that is the star here. Zeman used the prints of Gustave Doré combined seamlessly and magically with live action and animation. Colour palletes give an even more otherworldly feel to the visuals. No CG here, just inventive and unusual ways to get the effect he wanted, a man after my own heart.

The story, although following the outline of the original and using many vignettes from it, also adds references to Cyrano de Bergerac's visit to the moon, Jules Verne's "From the Earth to the Moon" and a tip of the hat to 60s sci-fi. Strange, funny and always unexpected, and even the music is a surprise! I had no idea it even existed, and it was a complete revelation to me. It felt like coming home. I used vintage prints exclusively as backgrounds in "Essentially Alys" and "Moonflower", and had a complete moon-trip story arc in my web series, with references to Cyrano, Verne, etc., so I was literally glued to the screen taking in all of the details. He is often called the Czech Méliès due to his style of mixing animation and effects with live action. Since writing the above I was also able to see his 1958 "Invention for Destruction" (also known as "Deadly Invention") in another beautifully restored print. Based on the writings of Jules Verne, Zeman again used vintage prints (in this case, Victorian line illustrations from the books) mixed with live-action to stunning effect. You always know that you're in a make-believe place, but paradoxically it seems very real, especially if you grew up readings books with this type of illustration (as I did).

Zeman's work impressed and/or influenced the likes of Terry Gilliam, Jan Švankmajer, Ray Harryhausen, Wes Anderson and Tim Burton (and also apparently inspired admiration from Pablo Picasso, Charlie Chaplin and Salvádor Dalí in his own time)! Guess I'm in good company singing his praises.

There is now a museum to him in Prague; another reason to travel again!

On Music and Film 1

You've all seen that example of a very exciting and tense scene from a film shown without its accompanying music and sound effects and then with them. Sometimes it might be a very emotional scene with heart-tugging music (and without). When you see this for the first time, it's almost shocking how unexciting or even uninteresting the version without might be. Music/sound plays a huge part in visual storytelling. Sure, "silent" movies didn't have them...or did they? There was always some kind of accompanying sound with the film, sometimes even sound effects performed live. Small theatre ensembles or soloists gave rise to the extremely versatile theatre organ, which was virtually a one-person band, complete with its own sound effects. Sure, the efficacy of the music's emotional response would vary from theatre to theatre depending on the performer, but the films were almost always projected with sound accompanying...it would have been weird otherwise. Case in point - a friend of mine attended a recent screening of a silent soundless film in a packed theatre. She said it was almost creepy how quiet it was and how everyone in the audience was very uncomfortable in their efforts not to make any noise, either - not cough, clear their throats, move in their seats, breathe loudly. Now that would have been a pretty interesting situation if it was the filmmaker's intention to cause this discomfort or awareness of one's surroundings, manipulating the audience, but this was a vintage film which was projected soundlessly, it seems, simply out of pure laziness. It was a blessedly short film. There are silent soundless films made today, of course, but usually for specific, typically noisy venues, like projected in public areas, on elevators, etc. Then there the amazing modern (1970s) completely silent films of Chantal Ackerman which I'll touch upon in Part 2 of this essay.

[HUGE ASIDE: A growing number of people watch videos silently on smaller devices when out and about, even without headphones/earbuds. Subtitles fill in the gaps. Fine for informational work; not sure what to make of this trend for scripted series. Then there are those who watch with sound and no earbuds in public places. This. Must. Stop.]

The reverse is music made for films without the visual aspect. Brian Eno's Music for Films (1978), for example, is a brilliant collection of very short pieces evoking imaginary films (although Eno's intention was for them to actually be used in films). Some of these pieces were used in films, before the public release of the album and since, but the music came first without an actual physical visual stimulus. It's an interesting concept, and one not too unfamiliar to the small independent filmmaker who may get their music from sites where generic music for purchase is categorised by genre, emotion and intent. Full movie soundtracks are a big part of the post production marketing of modern films as well, especially those films with songs or one particular song by a popular artist. These albums really allow people to relive favourite movies without actually watching them. (I'd be curious to know if listening to one of these albums without having seen or knowing anything about the connected film would give the same emotional response without having the story and/or visuals in one's mind's eye.)

This entire preamble is simply leading up to me saying that music and sound are HUGE parts of my filmmaking.

Part of my past training was as a musician (a harpist and violinist specifically, and also multiple instruments in some early music ensembles). I eventually got into composing for the harp (and other instruments), recording two CDs of original music. These have proved indispensable in my filmmaking, and I now realise that my compositions all came from some kind of visualization in my mind while composing or are evocative in other ways; it's almost like they were written with the future filmmaker Me in mind (although I don't think there was even the germ of that possibility in my mind at the time). It's also kind of nice not having to worry about copyright when designing the sound for films! In some cases, the music is the catalyst for the film. When planning "And She Rode Forth....", for example, I edited and arranged the music first (it was originally based on the Eowyn story from Lord of the Rings), then built the animation around the rhythm and duration of the piece. I also arrange classical/early pieces (public domain) to suit my needs. Many of my very short 1-minute films feature such arrangements. It's interesting to score these quite differently than for their intended instruments to give completely different interpretations of them.

On Music and Film 2

In part 1 of "On Music and Film" I touched briefly on Chantal Akerman's soundless films from the 70s. "Room" (1972) was one of her earliest films, and is 11 minutes of a camera panning 360 degrees around a room several times, in complete silence. I wasn't that taken with it, so the prospect of seeing "Hotel Monterey" (also 1972), coming in at a little over an hour, didn't really excite me...but it was a revelation. Soundless again, we start in the lobby of the old hotel. There are people, almost like part of a still life. But as you begin exploring the now-empty hallways in long dollies forward and backwards, it actually takes on its own rhythm, becomes compelling and, at times, filled with a sense of foreboding. Proceeding down the hall at an almost imperceptible pace, you are entering the unknown. Pulling back down the hall you are now relieved to be passing back through the familiar. The hallways are fairly dark and you eventually get a sense of endless night. Then, you dolly down a hall and discover the edge of a window! There IS an outside world! It is dawn. You end up on the roof, panning 360 around other rooftops and out over the landscape into the clouds. It is only then that you realize you have travelled from the very bottom of this hotel up through to the sky (like returning from the underworld). I keep saying "you" because in this case you are the camera and the camera is you. It's a contemplative and strangely mesmerizing work, and one in which the audience is not manipulated by mood-altering music or sounds...and is definitely not for everyone.

Then there is the polar opposite: cases in which the music is so meshed with the visuals that they are one. "Koyaanisqatsi" (1982) is almost the antithesis of Akerman's film. With music by Philip Glass and directed by Godfrey Reggio, the once-beautiful and inspiring world is seen as spiralling out of control. It's a "message" film (while "Hotel Monterey" is simply an experience), but the theme of life out of balance (that's what the Hopi word of the title means) draws you in completely. Glass' music is quite incredible and paired with the visuals (which are jaw-dropping) becomes quite awe-inspiring. It's an amazing pairing.

These two films are both without dialogue (except for some of the Hopi prophecies sung in Hopi), yet two more different films you could not see. One soundless, one relying on sound; one almost timeless, one speeding through time; one a finite and very personal fraction of time and space and the other a vast expanse of those...and yet they are oddly similar as you are drawn into an experience that is both mesmerizing and powerful.

Lotte Reiniger, Animation Pioneer

The name of Lotte Reiniger isn't a household one, but it should be. In a career spanning from the 1920s through the late 70s, she has the distinction of creating the first animated feature, a "silhouette" film based on a combination of stories from the Arabian Nights, "The Adventures of Prince Achmed" (1926) showcasing her life-long interest in shadow puppets. It is elegant and quite avant-garde for its time, almost Expressionist, although the story is a bit incomprehensible at times. She also developed a multi-plane camera for animation work long before Disney. If the opportunity arises to see the film, grab the chance.

-AR00XM6XBOSxWkLQ.jpg)

-AR00XM6XBOSxWkLQ.jpg)

Low resolution image from "Prince Achmed" from Wikimedia.

Using backgrounds of pure colour, the intricate black silhouettes are beautiful (still looking for a screenshot of good resolution). Subconsciously, her work was a bit of an inspiration for parts of my film "And She Rode Forth...." as you can see below!:

.....but my Heroine is considerably more gutsy than the princess in Achmed!

After realizing that "The Adventures of Prince Achmed" (1926) was on the Criterion Channel, we settled in to watch it again...it had been many, many years! The print was beautiful, with richly coloured backgrounds making the silhouettes stand out in all of their (considerable) glory. It's a visually stunning film, and quite ingenious in the ways the director worked out various effects. The cutouts are so incredibly intricate and gorgeous! The story, well...based on a mixture of stories from The Arabian Nights, there are manly heroes, fainting princesses, an evil magician and a pompous Caliph. At first you think there are no strong women, but then....enter the Witch! And this bizarre, ogre-like creature becomes The Hero of the whole story, saving the protagonists (both male and female) many times, vanquishing evil and making for a happy ending (for everyone except the evil Magician, of course!). There are even some funny bits in the film. So, although dated (especially in the representations of various people), I really do recommend watching this, the earliest surviving animated feature ever made, for the sheer technical skill and wondrous experimentation in fimmaking involved.

The Great Ray Harryhausen

I had been planning this essay for a while when suddenly Harryhausen's name was all over the place in posts, news releases and websites. Why? The next year (2020) was the centenary of his birth, so celebrations would ensue. Perhaps the main event was the huge show at the National Galleries of Scotland, Ray Harryhausen, Titan of Cinema , which looked like would be quite incredible, but other surprises were planned by The Ray & Diana Harryhausen Foundation. I'm not going to go into the details of his life and career as you can get all the info you need on Wikipedia or the website of the aforementioned Foundation (which, by the way, is a registered Scottish charity, so that explains the huge exhibit in Scotland). Instead, I'm just going to muse a bit on the great man's influence on both stop motion and me and mention my favourite works by him.

The foremost film in my mind when Harryhausen's name is mentioned is the 1963 Jason and The Argonauts. I can't tell you the impact this film had on me when I first saw it, and it's one of the very few movies that I could still watch again and again. It showed me that you could make fantasy come alive, make anything come alive through stop motion (although I didn't even know what that was back then). Harryhausen's films were frequently scored by Bernard Herrmann and the ominous music just enhanced the visuals. (Believe it or not, I have a scratchy old LP of the score to Jason!) The most terrifying moment for me is not the army of skeletons even though they are technically one of the most brilliant things the master ever did (and the sound they make as they clack menacingly at Jason still makes my hair stand on end), but rather the titan Talos. The shrieking metallic creaks as he comes to life and suddenly looks down at the miniscule humans below him...he seems like a force of nature; unconquerable. I'm getting the creeps even as I write this. Of course, it's all matter of when I first saw this film (at a very impressionable age) that has made it a lasting memory. Getting back to the army of skeletons, I remember reading an interview with Harryhausen a while back, and he was talking about filming the scene with several skeletons at once. Now if you don't know how stop motion is done, find out because it's important to this story! He had the scene set up and was painstakingly moving each joint of each skeleton in turn when the phone rang...he went to answer it, and by the time he got back he forgot where he was in the sequence! This is the days before digital, so he couldn't just scrub back to see where he was; he had to start over! Yes, all of his work was done on film. Both Talos and the skeletal army appear in virtually every top-10 list of Harryhausen's creations; usually the army justifiably holds first place.

Harryhausen's influence on stop motion and filmmaking in general is immense. He built his own characters and sets (and they aren't huge, making it much more difficult to manipulate). The influence his fantastic vision had on a lot of other filmmakers is undeniable; as the foundation's website states: "Steven Spielberg, Peter Jackson, Tim Burton, James Cameron, Guillermo Del Toro, Nick Park and so many others have cited Ray as a major inspiration to their careers; George Lucas was quoted as saying “Without Ray Harryhausen, there would likely have been no Star Wars”."

How I Became a Filmmaker

At the very first film festival I attended (not that long ago!), I was dismissed as an "anomaly" when I tried to contribute in a filmmakers' discussion; my experiences simply didn't apply to the average (young) filmmaker. I was, of course, annoyed as it came from someone who was very condescending. At the same time, however, I almost wanted to thank him for giving me a term to describe who I am in the world of filmmaking (and, actually, in many aspects of life at large). I'm also an Oxymoron (as in, an "Old Newbie") and also an Amateur in the true sense of the word (from the French for "lover of").

It's a bit strange when you "become" something quite late in life - it's almost like you're supposed to settle on one or two things as an adult and stick with those. I was kind of forced to find something to funnel my creativity into when I became ill after retirement from my "regular" job as a teacher. I had to quit playing the harp (luckily, I had recorded two CDs of original music before this happened). I had to quit Iaido (Japanese sword training). I couldn't paint or draw. You know that old adage about some doors closing and others opening? I actually hate that adage, but it IS true in my case. Once we had stabilized the worst of that chronic illness, I had to find something to keep me from going mad. I found I could work at my computer for longer and longer periods. I had always had an interest in puppetry and so did some short tests of stop motion with a Godzilla action figure. That was the Eureka moment! I started playing around with software and learning the ropes. I found that many of my previous pursuits helped me a lot now; music for the films, drawing skills, costuming and puppet making, writing, etc. I developed skills in stop motion and 2D animation, mostly by the seat of my pants (hence the name of part of my filmmaking endeavours). I had found my niche, and it kept me from going crazy while learning how to deal with daily life all over again.

I now realize how lucky I am that I came to filmmaking quite late in life. Yes, you read that right. I would not want to be a young filmmaker trying to break into the business these days, especially in animation. I am also my own "boss", as it's only me working on these films; I do everything (that's also probably the control freak in me). I don't really worry about funding or distribution because mine are true shoestring projects and I don't really need to make a living at this. And it's fun. I'll still always be the anomaly at festivals, and believe me there is more than a little ageism at some of them, but you know what? I can deal with it.

So, that's me - Anomaly, Oxymoron, Amateur, Person-of-all-trades. And ( proud to say) Filmmaker.

The Uncanny Valley

"Uncanny Valley" - those words conjure up visions of a weird, magical and possibly somewhat dangerous place from a fantasy novel. In reality, the term came from an actual dip on a chart indicating a human observer's reaction and emotional response to something resembling a human being. As an object (say, a robot) approaches the semblance of a human but isn't quite human, we get a very strange and unsettling feeling about it. Something isn't right; it becomes eerie or creepy. We respond negatively to it. That is the Uncanny Valley. This concept was originally discussed by a Japanese robotics professor, Mashahiro Mori and the term first translated as "uncanny valley" by Jasia Reichardt. Of course, it is used when discussing robotics and AI, and there was an interesting study done where three versions of an entity were presented to people; a very realistic human lookalike robot, the exact same robot without the "skin" (so, just the mechanics) and the human on whom the robot was based. The lookalike caused a negative response while the skinless robot didn't, even though it was doing the exact same things as the lookalike. (I'm assuming everyone liked the actual human 😀).

So, why am I discussing robotics, of which I know nothing? Well, this concept of the Uncanny Valley actually applies to animation as well, especially with widespread use of advanced CGI. There are fairly recent instances where the response to "realistic" characters in animation have been negative; they've been described as "creepy", "eerie" or even "scary", when they are supposed to be anything but. It's a strange idea, this valley. If a character you create is just a bit on either slope you can usually escape that feeling, but miscalculate and let your character slide into the valley and your whole animated feature could get entirely the wrong response! It can be a real tightrope act. Next time you watch some animation using almost lifelike computer-generated characters, think about this and ponder where in the valley the animation resides.

On Inspiration

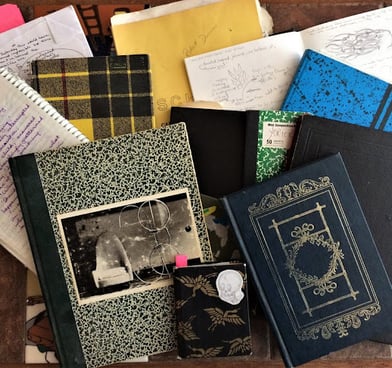

I have been a keeper of notebooks since around 1976. These aren't diaries, they aren't meant to be updated regularly and I'm not on any kind of schedule in regards to them, but I always carry a small notebook in my backpack or pocket and keep larger-format ones by my studio computer and on a bookshelf. For the last 45 years I have kept track of things and ideas that inspire or amuse me; originally they were for writing, sculptures and graphic arts projects (paintings, mostly). Sometimes they were just concepts or minutiae that I found interesting or mindboggling or fun. Sometimes they were full-blown scripts or drawings or glued-in clippings from other publications. These days they focus around my films...but it's always so strangely insightful to go back and read some of those earlier notes from when I was just taking my first questioning steps as an artist. I love the "who was this person?" moments I sometimes find or the "oh, yeah; I forgot about that" bits when I come across something that applies to what I'm doing right now. These days I suppose I could keep notes with pics on my phone, but somehow for me it isn't the same. The tactile part of scribbling in a notebook, doing a quick sketch or just putting down one or two words to indicate an idea is very, very appealing to me.

Above is a small selection of my notebooks, a ragtag collection to be sure. The oldest is the larger black one on the right, with my name in yellow wax pencil on the top right corner. The one with the spectacles is from the early 80s through early 90s. On one of my recent films, "Nightmares", I delved into the oldest notebooks and used sketches and writings from them in the backgrounds. It seemed appropriate because the nightmares from the film were ones I had around the time the notes were taken....definitely added to the creepy atmosphere, at least for me!

Planning out a film or webseries episode is usually done on a large sheet of paper, scribbled and highlighted and redone several times. I am positive that no one but me could possibly make head or tails from them.